Dutch start-up improves soil moisture monitoring

The Dutch start-up VanderSat has developed a method to radically improve the soil moisture data obtained from satellites. The resolution of such data used to be about 25x25 kilometres; VanderSat was able to improve this to 100x100 metres. This could have a huge impact on agriculture, weather prediction and climate research.

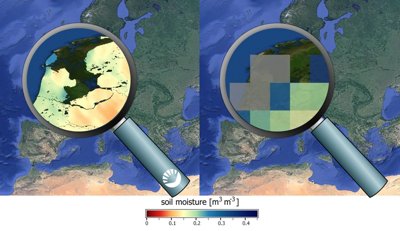

The approach is simple: instead of using data from a single satellite, data is combined from several different satellites. In other words, multisensor. ‘Each satellite provides images of soil moisture,’ explains Robbert Mica, co-founder of VanderSat. ‘The magic happens in the areas where different measurements overlap. Much more information is available in these areas, and by combining the data, you can obtain a higher resolution than a single satellite could provide.’

100 m VanderSat soil moisture versus currently available soil moisture satellite data

All of the satellite data is gathered in a big database. It is then processed to obtain soil moisture levels by applying a now patented method. What Google Maps is to people who want to look up a location or a route, VanderSat is to organisations who want to know the soil moisture content at a particular location.

Better weather prediction

The use of the improved data in the agricultural sector is self-evident. Farmers can use the improved soil moisture maps to increase yields by irrigating crops in the right spots and at the right time. However, there is more. For example, the risk of a thunderstorm is also affected by the amount of moisture in the ground. More accurate maps therefore help the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) to improve its local weather alert system.

The satellite data can also help predict natural disasters. Mica: ‘We now have over 30 years of satellite observations in the database. By analysing both past and present observations, the process preceding a drought can be followed much more accurately. This could improve the prediction of famine, for example. We are working together with organisations such as Cordaid, an NGO that provides humanitarian aid in areas hit by famine. We are also working with one of the largest irrigation companies in the world, which uses our data to provide a rapid response to impending drought.’

100% chance of getting caught

Through the SBIR-regeling, NSO has contributed to the development of an application for the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority that was presented last week. The application makes it easy for a user to daily check whether an area of land has been flooded. Farmers who receive compensation between the months of March and August for flooding their land currently have a 5% chance of being caught if they fail to comply with the agreements. Using the new application, this chance increases to 100%. It therefore represents a highly efficient way of fighting fraud by using data from the space industry.

The idea for VanderSat came about during a conversation between Robbert Mica and Richard de Jeu, associate professor in Earth Observation and Hydrology at VU Amsterdam. Together with his colleague Thijs van Leeuwen, de Jeu had developed the technology to considerably improve the resolution of satellite data. The idea was further developed as part of ATG Fast Forward, which invests in space technology start-ups that could have a large impact on societal themes.